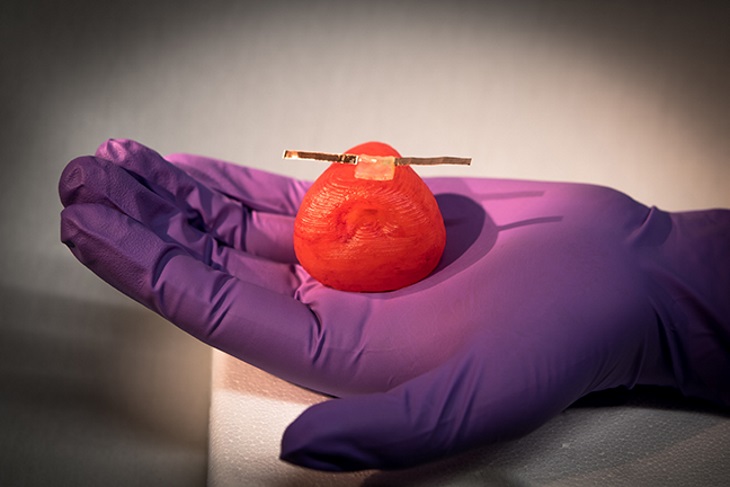

A team led by researchers at the University of Minnesota has 3D printed life-like artificial organ models that mimic the exact anatomical structure, mechanical properties, and look and feel of real organs. These patient-specific organ models, which include integrated soft sensors, can be used for practice surgeries to improve surgical outcomes in thousands of patients worldwide.

The research is reported in Advanced Materials Technologies, and the researchers are submitting a patent on this technology.

"We are developing next-generation organ models for pre-operative practice. The organ models we are 3D printing are almost a perfect replica in terms of the look and feel of an individual's organ, using our custom-built 3D printers," said lead researcher Michael McAlpine, an associate professor of mechanical engineering in the University of Minnesota's College of Science and Engineering.

"We think these organ models could be 'game-changers' for helping surgeons better plan and practice for surgery. We hope this will save lives by reducing medical errors during surgery," McAlpine added.

McAlpine said his team was originally contacted by Robert Sweet, a urologist at the University of Washington who previously worked at the University of Minnesota. Sweet was looking for more accurate 3D printed models of the prostate to practice surgeries.

Currently, most 3D printed organ models are made using hard plastics or rubbers, which limits their ability for accurately predicting and replicating the organ's physical behavior during surgery. There are significant differences in the way these organs look and feel compared to their biological counterparts. They can be too hard to cut or suture, and also lack an ability to provide quantitative feedback.

In this study, the research team took magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans and tissue samples from three patients' prostates. The researchers tested the tissue and developed customized silicone-based inks that can be ‘tuned’ to precisely match the mechanical properties of each patient's prostate tissue. These unique inks were used in a custom-built 3D printer by researchers at the University of Minnesota, who also attached soft, 3D-printed sensors to the organ models. They then observed the reaction of the model prostates during compression tests and on application of various surgical tools.

"The sensors could give surgeons real-time feedback on how much force they can use during surgery without damaging the tissue," said Kaiyan Qiu, a University of Minnesota mechanical engineering postdoctoral researcher and lead author of the paper. "This could change how surgeons think about personalized medicine and pre-operative practice."

In the future, researchers hope to use this new method to 3D print life-like models of more complicated organs, using multiple inks. For instance, if the organ has a tumor or deformity, the surgeons would be able to see that in a patient-specific model and test various strategies for removing tumors or correcting complications. They also hope to someday explore applications beyond surgical practice.

"If we could replicate the function of these tissues and organs, we might someday even be able to create 'bionic organs' for transplants," McAlpine said. "I call this the 'Human X' project. It sounds a bit like science fiction, but if these synthetic organs look, feel and act like real tissue or organs, we don't see why we couldn't 3D print them on demand to replace real organs."

This story is adapted from material from the University of Minnesota, with editorial changes made by Materials Today. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of Elsevier. Link to original source.