Researchers at Duke University have 3D printed potent electromagnetic metamaterials using an electrically-conductive material compatible with a standard 3D printer. This demonstration could revolutionize the rapid design and prototyping of various radio frequency technologies, including Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, wireless sensing and communications devices.

Metamaterials are synthetic materials composed of many individual, engineered devices called cells that together produce properties not found in nature. As an electromagnetic wave moves through a metamaterial, each engineered cell manipulates the wave in a specific way to dictate how the wave behaves as a whole.

This means metamaterials can be tailored to possess a range of unnatural properties such as the ability to bend light backwards, focus electromagnetic waves onto multiple areas and perfectly absorb specific wavelengths of light. But previous efforts have been constrained to 2D circuit boards, limiting the effectiveness and abilities of metamaterials and making their fabrication difficult.

Now, in a new paper in Applied Physics Letters, Duke materials scientists and chemists report a way to bring electromagnetic metamaterials into the third dimension using common 3D printers.

"There are a lot of complicated 3D metamaterial structures that people have imagined, designed and made in small numbers to prove they could work," said Steve Cummer, professor of electrical and computer engineering at Duke University. "The challenge in transitioning to these more complicated designs has been the manufacturing process. With the ability to do this on a common 3D printer, anyone can build and test a potential prototype in a matter of hours with relatively little cost."

The key to making 3D printed electromagnetic metamaterials a reality was finding the right conductive material to run through a commercial 3D printer. Such printers usually use plastics, which are typically terrible at conducting electricity.

While there are a few commercially-available solutions that mix metals in with the plastics, none are conductive enough to create viable electromagnetic metamaterials. And while metal 3D printers do exist, they cost as much as $1 million and take up an entire room.

That's where Benjamin Wiley, Duke associate professor of chemistry, came in. "Our group is really good at making conductive materials," said Wiley, who has been exploring these materials for nearly a decade. "We saw this gap and realized there was a huge unexplored space to be filled and thought we had the experience and knowledge to give it a shot."

Wiley and Shengrong Ye, a postdoctoral researcher in his group, created a 3D printable material that is 100 times more conductive than anything currently on the market; the material is currently being sold under the brand name Electrifi by Multi3D, a start-up founded by Wiley and Ye. While Electrifi is still not as conductive as regular copper, Cummer thought that it might just be conductive enough to make a 3D-printed electromagnetic metamaterial.

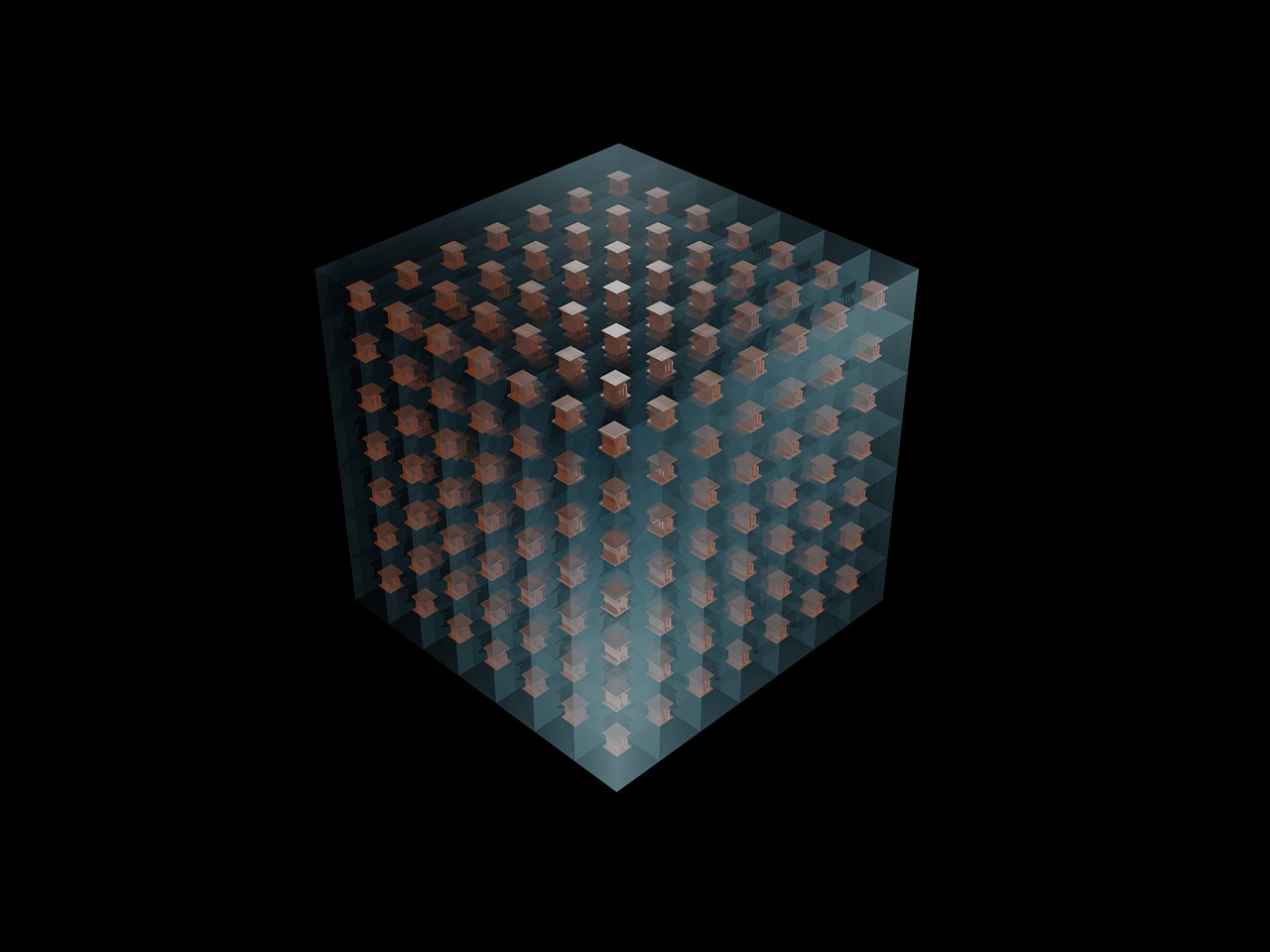

In the paper, Cummer and doctoral student Abel Yangbo Xie show that not only is Electrifi conductive enough, it interacts with radio waves almost as strongly as traditional metamaterials made with pure copper. And that small difference is easily made up for by the printed metamaterials' 3D geometry – the 3D printed metamaterial cubes interact with electromagnetic waves 14 times better than their 2D counterparts.

By printing numerous cubes, each tailored to specifically interact with an electromagnetic wave in a certain way, and combining them like Lego building blocks, researchers can begin to build new devices. For the devices to work, however, the electromagnetic waves must be roughly the same size as the individual blocks. While this rules out the visible spectrum, infrared and X-rays, it leaves open a wide design space in radio waves and microwaves.

"We're now starting to get more aggressive with our metamaterial designs to see how much complexity we can build and how much that might improve performance," said Cummer. "Many previous designs were complicated to make in large samples. You could do it for a scientific paper once just to show it worked, but you'd never want to do it again. This makes it a lot easier. Everything is on the table now."

"We think this could change how the radio frequency industry prototypes new devices in the same way that 3D printers changed plastic-based designs," said Wiley. "When you can hand off your designs to other people or exactly copy what somebody else has done in a matter of hours, that really speeds up the design process."

This story is adapted from material from Duke University, with editorial changes made by Materials Today. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of Elsevier. Link to original source.