"Bridging the gap between mom-and-pop anodizers and those larger operations that serve the Boeings of the world direct.” That is how Jeff Almeyda, president of Master Metal Finishing in Paterson, N.J., describes the niche market occupied by his firm—an operation specializing in proprietary aluminum anodizing processes and high-tech chromate conversion coatings. For him, it’s all about being in a position to tackle specialized jobs often eschewed by finishers chasing the commodity side of the business.

“If an anodizer is going to survive and thrive, it’s not going to be through the nickel-and-dime commercial jobs that are out there,” Almeyda explained. “Rather, it will be through investing in specialized, high-technology processes in order to cater to the market that requires those services.”

That pretty much explains Master Metal Finishing's winning formula to a tee. Take a thorough tour through the company’s 22,000-square-foot plant, and one can readily see this formula at work. Specializing in aluminum anodizing, hardcoating, and chemical film treatments, Master Metal Finishing employs what it calls a “synergistic combination of ultra-tight chemistry and performance parameters with a state-of-the-art computer anodizing system.” (Translation: highly guarded proprietary processes.)

Without divulging too much, Almeyda explained how this combination of various chemistries and processes magically allows the use of significantly higher current densities than conventional anodizing systems. The end result, he says, is a harder, clearer film that can be deposited much more quickly than previously possible. Throw in some advanced computerized process controls, coupled with spectra-photometric color analysis for some real razzle-dazzle, and what you get is a consistently high finish quality and quicker turnaround—attributes any demanding customer would love.

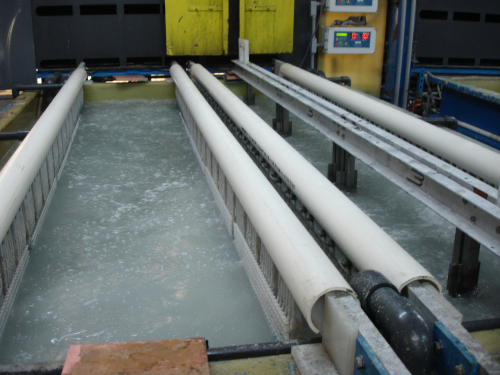

“The basic overriding theme when I put this place together was to optimize every aspect of the operation from incoming RO/DI water, to the pretreatment, to the pulse rectifiers, to the triple-flow rinse systems and the chemistry,” Almeyda said. In addition, the equipment allows operators to record every load that goes through the system. “Not only are the loads logged by the operators going through, but also by the actual computer system itself,” he explained.

Another illustration of the technology at work: each rectifier’s output is recorded in real time to a hard disc, showing operators the volts and amps (all time-stamped). The benefit: the company has traceability back across time. So, an operator can go back to that particular load and see the process parameters as if it were real time.

But perhaps the ultimate example of the perfect marriage of chemistry and processes is the quality of the finish itself. Dubbed “Mastercoat,” Master Metal’s signature finish touts wear resistance and aesthetic attributes that exceed some already demanding military specifications.

“In the old days, we used to brush the parts, black anodize them, and then put a clear black lacquer on them for brightness and also for a little more durability,” said Kevin Almeyda, vice president. “But with our new process, we’ve been able to eliminate the lacquering stage entirely. We’re basically providing our customers with a hard black coating (“hard” Type 2 or a “decorative” Type 3) with better corrosion and abrasion resistance, and a part that’s consistent in appearance. For the customer it’s also a finish with a tighter dimensional tolerance.”

Clearly all these bells and whistles require not only intensive R&D but also significant capital investment. (Almeyda estimates that more than $1.5 million has been doled out thus far to spruce up the facility.) Many would see this as bucking the industry trend. “No new shops are going up these days,” said a fabrication expert familiar with Master Metal’s operation. “If someone is expanding, it’s often a compromise based on existing facilities. And when there are new installations, most of the time they are OEMs,” the source said.

From Jeff Almeyda’s perspective, Master Metal Finishing is the only significant, new job-shop facility in the Northeast region in probably more than 20 years—at least by his count. “If anything, my research tells me guys are getting out of the business as opposed to investing millions into new technology.”

One customer who can attest to the by-products of this investment is Middle Atlantic Products, a Fairfield, N.J.–based manufacturer of electronic audio equipment, power distribution paraphernalia, and the like. The custom finish that Master Metal provided was so durable that the client created a performance demonstration video showing how finished panels can stand up to abuse without any discernible evidence of finish compromise.

If you thought that was impressive, you would be even more wowed by the process required to strip a product incorporating this stubborn finish. “You can’t just strip it—you have to leave it in the deoxidizer for about 15 minutes to penetrate the pore structure before you get any access,” Almeyda said. Another example of Mastercoat’s tenacity: efforts by conventional CO² lasers to engrave the surface of the hard anodize coat are only marginally effective; doped fiber lasers are required.

Satisfied clients are singing the praises. “We recently switched to the Mastercoat finish on all of our chassis, drawers, and panels,” said Frank LoBrace, CPIM, director of purchasing, Middle Atlantic Products, Inc. “The brightness allowed us to eliminate an entire secondary operation, thereby improving throughput. The increased durability of the finish also helps us market a superior-quality message to our customers.” The same can be said for Holbrook, N.Y.–based B/E Aerospace, Inc., the world’s largest manufacturer of air-handling and lighting systems for commercial and private aircraft. “Our clientele are very sensitive to quality in finishes and demand the very best,” said Gary Hancock, vice president of operations. “Master Metal Finishing has been able to support us in our goal to always be the best in the industry.”

Technical Know-how

Of course, all the advanced technology in the world cannot be fully utilized without the high level of technical expertise required to implement and maintain it. And considering the cumulative experience of the 17-member staff at Master Metal Finishing (see “Historical Perspective” sidebar), that’s something certainly in abundant supply at this facility. For Almeyda, it all starts with a solid working knowledge of all things related to aluminum anodizing. On that point, he unselfishly defers to his long-time mentor Fred C. Schaedel, a widely recognized authority on aluminum anodizing processes.

|

“Fred is brilliant,” Almeyda said of the anodic tech support chief for Alpha Process Systems based in Westminster, Calif. “He’s one of the men who helped develop white anodizing for NASA!”

Typically, when you find an anodizing expert, he or she will recite back to you all the basics they learned in anodizing school, Almeyda recalled: ‘70 degrees plus or minus, 2 degrees Fahrenheit, 12–15 amps per square foot, etc., etc.’ “Well, Fred took it a step further. The anodizing chemistry he developed is more than four times more efficient at removing heat from the base of the pore structure than anyone else’s. This allows for high-power, pulsed rectification.”

Schaedel’s excitement about the achievements his protégé has made in a relatively short time is palpable. Not only is he enthralled with all the new facets of the plant, but he’s also pleased that someone is finally listening. “Everybody tells me we can’t do that because of this or that,” Schaedel told Almeyda recently, citing objections to some of his novel recommendations regarding improving traditional anodizing procedures. “My emphasis is the complete system, meaning putting in the additive along with the pulse rectification—not one or the other. Or they put in the additive but only one-third of what I tell them to. And then they wonder why they’re not getting the results that they want.”

|

Thankfully, Almeyda is taking heed. More importantly, he thrives on the inner workings behind the process. “I was a pre-med student at Columbia University, so the science part of organic chemistry doesn’t throw me,” he said. “Since I started learning about anodizing, I also wanted to find out what was happening inside the anodize tank instead of just going through the motions.”

Outlook

As Almeyda contemplates the “next big thing” that might spring out of ongoing research, development, and experimentation at Master Metal Finishing, it’s hard to contain his enthusiasm. That’s especially true when he talks about the future possibilities for anodizing. Current projects include examining the prospects of what his company can provide using its hard clear coating and chemical polishing processes, and he’s also looking to devise a feasible replacement for bright chrome on automotive trim. In addition, the firm is currently setting up an R&D line to test electrolytic black for bright finishes. (Harley Davidson, among others, Almeyda notes, is looking for a shop that can deliver a bright, black aluminum-anodized part that can withstand 800 degrees. Although he’s convinced beyond a doubt that “no dye on Earth can accomplish this,” he is sure that the solution will most certainly entail an electrolytically colored process.)

From an operational perspective, Master Metal Finishing should be fully automated within one to two years. As it stands now, the company utilizes a PLC-based system that controls all the tank temperatures, pulse controls, pollution controls, spray headers, mist-elimination systems, and so on. Almeyda also plans to continue applying lean manufacturing processes to virtually all facets of his business. It’s a movement, he says, that’s being dictated by both competitive pressures as well as ever-rising manufacturing industry benchmarks.

“Processes are doubling in speed every 18 months, so you need to have automation and pull the variables out of your line-up,” Almeyda noted. “Also, you’ll need to be able to service at the highest level—that’s where the higher profit margins are.”

Operative word: “service.” For example, a manufacturing executive of a Fortune 500 company and potential Master Metal client recently told Almeyda that he hopes Master Metal succeeds because the [Fortune 500 firm] is “losing qualified sources for finishing.”

At the same time, Almeyda is also a realist. Given the current business climate and national economic trends, he is well aware that there are less total dollars out there than what was previously available. On the other hand, he knows there are also opportunities for those companies willing to bring themselves up to a new standard of finishing.

Take finishing complex alloys, for example. Most hard coat anodizers, Almeyda notes, have a tough time hard coating 2024 (a high-strength alloy used in aircraft parts) and 2011, an even more tricky metal to coat. But not for Master Metal. “So, right there you’re looking at specialized work that others simply cannot do,” Almeyda said.

Next up is Nadcap Certification—a plateau the company intends to reach within one year. That’s going to be an absolute “must” if Master Metal intends to pursue its stated goal of aggressively targeting the aerospace/airline sector.

“When I started in this business it was 99.9% quality; now it’s 0 defect,” Almeyda observed. “As an aerospace engineer once put to me: ‘If my plane has 60,000 parts and one out of every 1,000 is a failure, you’re going to tell me that this plane has 60 failures on it?’ That’s not acceptable!”

What’s also needed to ensure future success is a keener focus on short runs (as opposed to the more traditional long runs and high inventories). “In order to do that, you not only have to have a system that allows you to do the work but one that also records everything,” Almeyda explained. “It’s a matter of an across-the-board improvement and bringing up to what current manufacturing standards consider acceptable.” In simple terms, embrace “lean” manufacturing.

Master Metal’s projections are also aggressive when it comes to sales targets. Without revealing specific numbers, Almeyda would only say the company is looking at quintupling its sales from their current levels. If it were anyone else, some people would say he was vastly overreaching. But this is a true maverick that we’re talking about here.

“We have a tremendous amount of capacity because we’ve built for the future,” Almeyda said. “And the future is bright if you are willing to move with the times.”