By using an electrochemical etching process on a common stainless steel alloy, researchers have created a nanotextured surface that kills bacteria while not harming mammalian cells. If additional research supports early test results, this process might be used to attack microbial contamination on implantable medical devices and on food processing equipment made with the metal.

While the specific mechanism by which the nanotextured material kills bacteria requires further study, the researchers believe that tiny spikes and other nano-protrusions created on the surface puncture bacterial membranes to kill the bugs. The surface structures don't appear to have a similar effect on mammalian cells, which are an order of magnitude larger than the bacteria.

Beyond the anti-bacterial effects, the nano-texturing also appears to improve corrosion resistance. The research was reported in a paper in ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering by researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

"This surface treatment has potentially broad-ranging implications because stainless steel is so widely used and so many of the applications could benefit," said Julie Champion, an associate professor in Georgia Tech's School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering. "A lot of the antimicrobial approaches currently being used add some sort of surface film, which can wear off. Because we are actually modifying the steel itself, that should be a permanent change to the material."

Champion and her Georgia Tech collaborators found that the surface modification killed both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, testing it on Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. But the modification did not appear to be toxic to mouse cells – an important issue because cells must adhere to medical implants as part of their incorporation into the body.

The research began with the goal of creating a super-hydrophobic surface on stainless steel in an effort to repel liquids – and with them bacteria. But it soon became clear that creating such a surface would require the use of a chemical coating, which the researchers didn't want to do. Postdoctoral fellows Yeongseon Jang and Won Tae Choi then proposed an alternative idea of using a nanotextured surface on stainless steel to control bacterial adhesion, and they initiated a collaboration to demonstrate this effect.

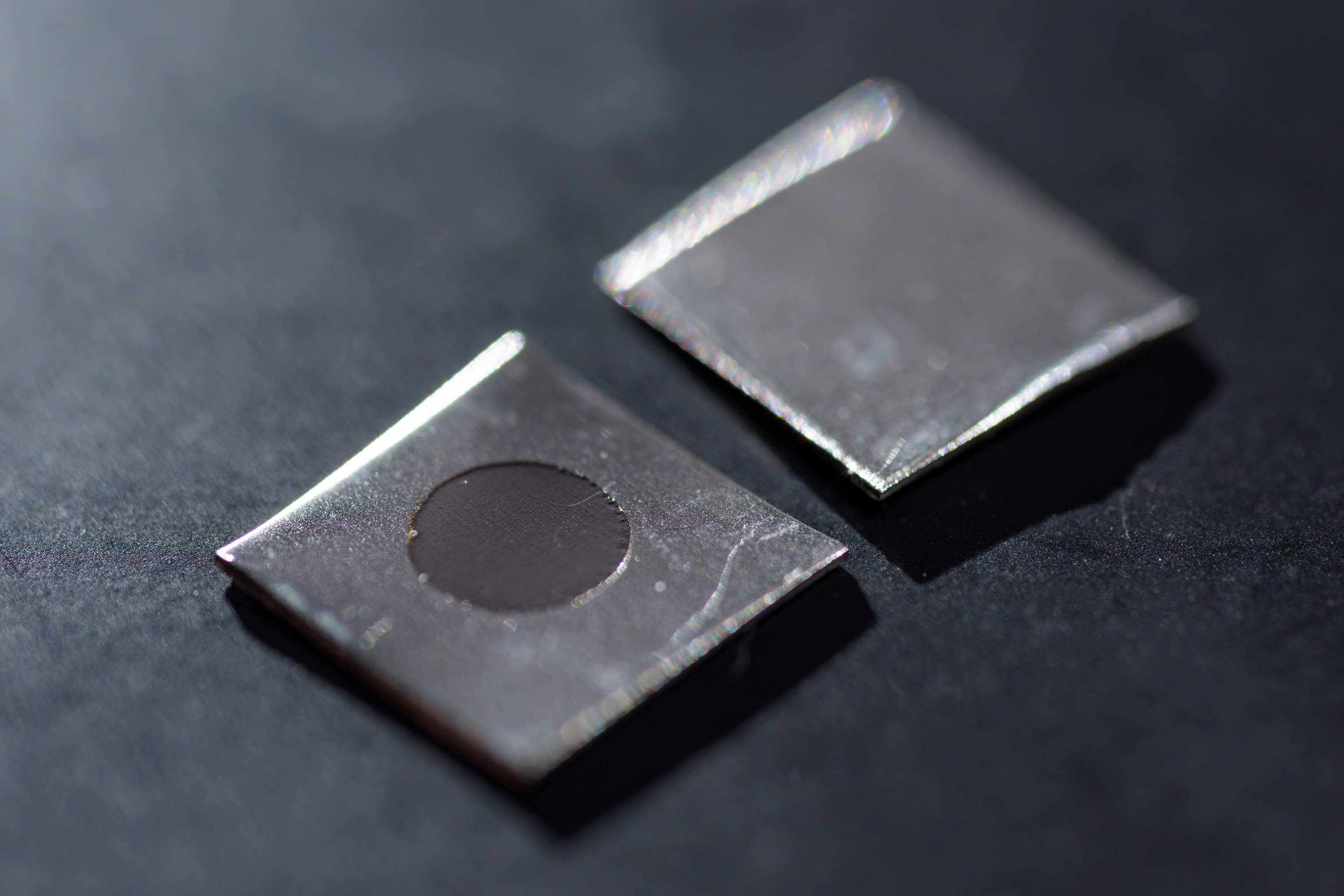

To produce a nanotextured surface, the research team experimented with varying levels of voltage and current flow in a standard electrochemical process. Typically, electrochemical processes are used to polish stainless steel, but Champion and collaborator Dennis Hess, a professor in the School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, used the technique to roughen the surface at the nanometer scale.

"Under the right conditions, you can create a nanotexture on the grain surface structure," Hess explained. "This texturing process increases the surface segregation of chromium and molybdenum and thus enhances corrosion resistance, which is what differentiates stainless steel from conventional steel."

Microscopic examination showed protrusions 20–25nm above the surface. "It's like a mountain range with both sharp peaks and valleys," said Champion. "We think the bacteria-killing effect is related to the size scale of these features, allowing them to interact with the membranes of the bacterial cells."

The researchers were surprised that the treated surface killed bacteria. And because the process appears to rely on a biophysical rather than chemical process, the bugs shouldn't be able to develop resistance to it, Champion added.

A second major potential application for this surface modification technique is food processing equipment. Here, the surface treatment should prevent bacteria from adhering, enhancing existing sterilization techniques.

The researchers used samples of a common stainless alloy known as 316L, treating the surface with an electrochemical process in which current was applied to the metal surfaces while they were submerged in a nitric acid etching solution.

On application of the current, electrons move from the metal surface into the electrolyte, altering the surface texture and concentrating the chromium and molybdenum content. The specific voltages and current densities control the type of surface features produced and their size scale, said Hess. He worked with Choi – then a PhD student – and Victor Breedveld, associate professor in the School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, and Preet Singh, professor in the School of Materials Science and Engineering, to design the nanotexturing process.

To more fully assess the antibacterial effects, Jang engaged the expertise of Andrés García, a professor in Georgia Tech's Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering, and graduate student Christopher Johnson. In their experiments, they allowed bacterial samples to grow on treated and untreated stainless steel samples for periods of up to 48 hours.

At the end of that time, the treated metal had significantly fewer bacteria on it. This observation was confirmed by removing the bacteria into a solution, then placing the solution onto agar plates. The plates receiving solution from the untreated stainless steel showed much larger bacterial growth. Additional testing confirmed that many of the bacteria on the treated surfaces were dead.

Mouse fibroblast cells, however, did not seem to be bothered by the surface. "The mammalian cells seemed to be quite healthy," said Champion. "Their ability to proliferate and cover the entire surface of the sample suggested they were fine with the surface modification."

For the future, the researchers plan to conduct long-term studies to make sure the mammalian cells remain healthy. The researchers also want to determine how well their nanotexturing holds up when subjected to wear.

"In principle, this is very scalable," said Hess. "Electrochemistry is routinely applied commercially to process materials at a large scale."

This story is adapted from material from the Georgia Institute of Technology, with editorial changes made by Materials Today. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of Elsevier. Link to original source.