This 3D printing process produces metal parts layer by layer using a high-energy laser beam to fuse metal powder particles. When each layer is complete, the build platform moves downward by the thickness of one layer, and a new powder layer is spread on the previous layer.

While this process is able to produce quality parts and components, residual stress is a major problem during the fabrication process, because large temperature changes near the last melt spot (rapid heating and cooling) and the repetition of this process result in localized expansion and contraction, which can both create residual stress.

Residual stress can impact on mechanical performance and structural integrity and cause distortions during processing resulting in a loss of net shape, detachment from support structures and, potentially, the failure of additively manufactured (AM) parts and components.

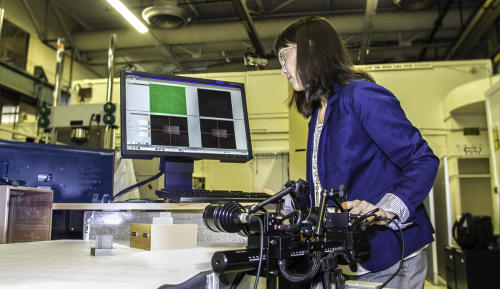

Dual camera set up

A research team led by engineer Amanda Wu, has developed a residual stress measurement method that uses traditional stress-relieving methods (destructive analysis) and digital image correlation (DIC) to provide faster and more accurate measurements of surface-level residual stresses in AM parts.

The team used DIC to produce a set of quantified residual stress data for AM, exploring laser parameters. DIC is an image analysis method in which a dual camera setup is used to photograph an AM part once before it’s removed from the build plate for analysis and once after. The part is imaged, removed and then re-imaged to measure the external residual stress.

In a part with no residual stresses, the two sections should fit together perfectly and no surface distortion will occur. In AM parts, residual stresses cause the parts to distort close to the cut interface. The deformation is measured by digitally comparing images of the parts or components before and after removal. A black and white speckle pattern is applied to the AM parts so that the images can be fed into a software program that produces digital illustrations of high to low distortion areas on the part’s surface.

Neutron beam

In order to validate their results from DIC, the team collaborated with Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) to perform residual stress tests using a method known as neutron diffraction (ND). This technique, performed by researcher Donald Brown, measures residual stresses deep within a material by detecting the diffraction of an incident neutron beam. The diffracted beam of neutrons enables the detection of changes in atomic lattice spacing due to stress.

The LLNL team’s DIC results were validated by the ND experiments, showing that DIC is a reliable way to measure residual stress in powder-bed fusion AM parts.

Their findings were the first to provide quantitative data showing internal residual stress distributions in AM parts as a function of laser power and speed. The team demonstrated that reducing the laser scan vector length instead of using a continuous laser scan regulates temperature changes during processing to reduce residual stress. Furthermore, the results show that rotating the laser scan vector relative to the AM part’s largest dimension also helps reduce residual stress. The team’s results confirm qualitative data from other researchers that reached the same conclusion.

Adjusting parameters

By using DIC, the team was able to produce reliable quantitative data that will enable AM researchers to optimally calibrate process parameters to reduce residual stress during fabrication. Laser settings (power and speed) and scanning parameters (pattern, orientation angle and overlaps) can be adjusted to produce more reliable parts. Furthermore, DIC allowed the Lawrence Livermore team to evaluate the coupled effects of laser power and speed, and to observe a potentially beneficial effect of subsurface layer heating on residual stress development.

“We took time to do a systematic study of residual stresses that allowed us to measure things that were not quantified before,” Wu said. “Being able to calibrate our AM parameters for residual stress minimization is critical.”

According to LLNL, the findings will eventually be used to help qualify properties of metal parts built using the powder-bed fusion AM process.

The results were reported in an article titled “An Experimental Investigation Into Additive Manufacturing-Induced Residual Stresses in 316L Stainless Steel” that was recently published in the journal Metallurgical and Materials Transactions.