The U.S. Code defines a hazardous waste as:

- a solid waste, or combination of solid wastes, which because of its quantity, concentration, or physical, chemical, or infectious characteristics may—

- a. cause, or significantly contribute to, an increase in mortality or an increase in serious irreversible, or incapacitating reversible, illness; or

- b. pose a substantial present or potential hazard to human health or the environment when improperly treated, stored, transported, or disposed of, or otherwise managed.i

Further, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act or RCRA defines hazardous wastes as:

- Wastes that are contained on an EPA List ( e.g., electroplating wastes like F006, F009, and F019), or

- Wastes that are characteristically hazardous (e.g., corrosive, ignitable, reactive), or

- Wastes that are mixtures of hazardous wastes and solid wastes (e.g., a mixture of F019 wastes and filters), or

- Wastes that are derived from hazardous wastes (e.g., wastewater treatment plant sludge from a process that meets the definition of a F006 waste).ii

Metal finishing processes frequently generate objectionable by-products that might include, for example, air emissions, wastewater treatment plant sludges, characteristically hazardous corrosive wastes, organic halogenated solvents, and cyanide. An overview of the wastes typical of the metal finishing industry is provided in Table 1.

It is not unusual for waste disposal to be one of the more costly operating expenses at a metal finishing plant. Managing hazardous wastes at a plant is also a very resource-intensive activity. Tasks such as labeling, storing, manifesting, training, signage, spill response, closure, and long-term liability are all integral to the proper management of hazardous wastes. The most common waste codes applicable to the metal finishing sector are F-Codes F006, F009, and F019. F006 and F009 deal with electroplating while F019 pertains to the chemical conversion coating of aluminum. It is not uncommon for facilities to spend well over $100,000/year dealing with these F-coded wastes. Disposal costs, including all the tasks referenced above—plus transportation and state fees—can run to well over $200/ton.

One way around these high disposal costs is to go through the process of excluding or delisting the waste from consideration as hazardous. Regulations at 40 CFR 260.22 outline in general what is required to delist a waste. Major components of a delisting include: identifying constituents of concern, preparation of a sampling and analysis plan, preparation of a quality assurance project plan, close coordination with the regulatory authority having jurisdiction (either an EPA Region or a State agency), and publication of proposed and final rules in the Federal Register.

Hazardous Waste Delistings. Delistings are primarily handled out of an EPA Region with Regions 4, 5, and 6 performing the most delistings. Some states, however, have jurisdiction to perform delistings (e.g., Georgia, Indiana, and Pennsylvania) and in such cases you will want to coordinate your activities with the state environmental agency.

There are a number of resources you will want to review prior to undertaking a hazardous waste delistings. A few of these are listed in Table 2. Major Steps in a Delisting. There are at least 12 (twelve) major steps in a typical delisting. These major steps, along with some information on timing, are included in Table 3. It is assumed that close coordination with the controlling regulatory agency will be a part of every step identified in Table 3.

Steps 1 and 2 — Identifying Constituents of Concern. There is perhaps no other step in securing a delisting that is more important than identifying the constituents of concern (COC). The process involves reviewing a number of regulatory lists (e.g., Appendix VIII and Appendix IX)iii to determine if a given constituent is in the subject waste. For one list of chemicals in particular, Appendix VIII, it is difficult to identify all of the chemicals on the list because either standard methods do not exist, or the procedure is incredibly expensive, or the method will not work in the matrix of the waste sample. Either way, it will be important to establish with the regulatory authority the total universe of chemicals to include in your review. One thing the petitioner (the entity conducting the delisting is termed the petitioner) should keep in mind is that it is your responsibility to provide a complete and thorough characterization of your waste. Ultimately, it is not uncommon for the petitioner and the agency to settle on analyzing for all constituents (~ 222 chemicals) on Appendix IX.

An important document that the petitioner must prepare is the Sampling and Analysis Plan (SAP). The SAP lays out specifically what will be analyzed for, the number of samples, the analytical techniques, and data analysis methods that will be used. The SAP is a living document in that the petitioner and the agency will probably go through several iterations before a final SAP will be produced. You cannot proceed with the overall process until you have an agreed upon SAP.

There are lists of chemicals that are expected to characterize certain wastes (e.g., petroleum refinery wastes) and those chemicals should be incorporated into your SAP.

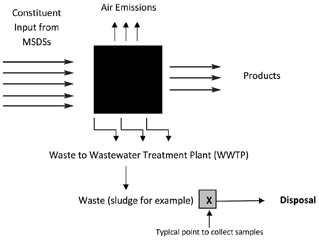

Steps 3, 4, and 5 — Engineering Analysis, Generator Knowledge and Identifying Analytes. There are several additional ways to modify the COCs list. One way is to conduct an engineering analysis that essentially involves conducting a mass balance around major process units at the facility undergoing the delisting. This is typically done by using a plant’s chemical management system to assemble the list of potential inputs to a process. Essentially you take a process unit and treat it as a black box with chemical inputs, and product, and waste outputs. Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDSs) are extremely useful in conducting this phase of the analysis. By lining up the constituents, as displayed on an MSDS, you can approximate a mass balance around a given process unit. An example of this is provided in Figure 1.

As with the characterization of any RCRA waste, the petitioner can use generator knowledge to add to or subtract from the COC list. Frequently, generator knowledge is the best type of information to use in making a determination as to what to test for or what not to test for. For example, a person familiar with a plant’s layout will likely be able to know quite quickly rather or not a particular waste flows into a sewer pipe that eventually makes it to the WWTP.

You are now at a point where the list of COCs should be fairly complete and you have identified all analytes that may be in the waste. Steps 6 and 7 — Select Analytical Methods and Prepare QAPP. The standard reference for collecting and analyzing waste samples is the series of some 200 methods referred to as SW 846. iv This again is a very important point of coordination with the agency so that everyone is on the same page when it comes to not only what is being analyzed for but how it will be determined. What method is selected can frequently determine the sensitivity of the final analytical result. For example, you would want to select a method that had a reporting limit of 0.001 mg/l over one that had a limit of 0.1 mg/l if the point for comparison from the risk assessment model (see later section on the use of the DRAS model) was 0.01 mg/l.

In conjunction with selecting the analytical methods it is also very important to decide upon the quality assurance and quality controls that will accompany each piece of data. A Quality Assurance Project Plan (QAPP) describes the activities of an environmental data operations project involved with the acquisition of environmental information whether generated from direct measurements activities, collected from other sources, or compiled from computerized databases and information systems.v The QAPP documents the results of a project’s technical planning process, providing in one place a clear, concise, and complete plan for the environmental data operation and its quality objectives and identifying key project personnel. Steps 8 and 9 — Data Collection and Analysis. The SAP will specify the what, where, and how of collecting representative waste samples. The term representative here is very important in that above all else the samples collected need to truly represent the waste. Factors such as waste variability over time, production variables, waste treatment variability, and potential for system upsets are all important to account for in your approach to data collection.

Data analysis can be quite complicated or rather straightforward. Typically if you have a large dataset, say, greater than 15 samples, you can perform fairly robust statistical evaluations using some rigorous data mining efforts. The agency should be consulted beforehand regarding what approach they will endorse regarding data analysis. If your budget will only accommodate a small sample size, say, six (6) samples, the agency will require that for a given analyte the maximum observed value should be used versus, for instance, a mean value or some other statistically derived exposure endpoint.

Once you have analyzed the data and arrived at an exposure point concentration for each of the constituents of concern, you are ready to run the DRAS model. The Delisting Risk Assessment Software (DRAS) model was developed by EPA Region 6 and improved and modified by Region 5. DRAS performs a multi-pathway and multi-chemical risk assessment to assess the acceptability of a petitioned waste to be disposed into a Subtitle D landfill or surface impoundment. DRAS executes both forward- and back calculations. The forward calculation uses chemical concentrations and waste volume inputs to determine cumulative carcinogenic risks and hazard results. The back-calculation applies waste volume and acceptable risk and hazard values to calculate upper- limit allowable chemical concentrations in the waste.vi The DRAS 3.0 model is available on EPA Region 5’s website. The results of running the DRAS model ultimately determine whether you will be able to get your waste delisted. If you pass the DRAS model then you incorporate your findings into your petition. If you fail the DRAS model (i.e., you exceed a DRAS calculated limit for a given chemical) you need to consult with the agency to determine next steps. Steps 10, 11, and 12 — Preparing and Submitting the Petition and Publication in the Federal Register. The culmination of all of the previous steps is the preparation of a delisting petition. The petition is the petitioner’s main product for delivery to the agency for review and consideration. The major sections of a delisting petition are outlined in Table 4.

A typical delisting petition will be well over 500 pages and frequently over 1,000 pages long. The petition is aimed at providing all of the information necessary for the agency to make an informed decision regarding the requested delisting for the waste. CONCLUSIONS For metal finishing plants with significant generation rates of hazardous wastes, it may be wise to look at a hazardous waste delisting as a way to avoid high disposal costs. Once a facility is delisted the subject waste can be disposed in a Subtitle D landfill where the costs are frequently 4-8 times cheaper. Further, many of the headaches that go along with handling hazardous wastes (e.g., manifesting, training, spill response, closure, etc.) go away or are substantially reduced.

| Process | Material Input | Air Emission | Process Wastewater | Solid Waste |

| Surface Preparation | ||||

| Solvent Degreasing and Emulsion Alkaline and Acid Cleaning | • Solvents • Emulsifying agents • Alkalis • Acids | • Solvents • Caustic mists | • Solvent • Alkaline • Acid wastes | • Ignitable wastes • Solvent wastes • Still bottoms |

| Surface Preparation | ||||

| Anodizing | • Acids | • Metal ion-bearing mists • Acid mists | • Acid wastes | • Spent solutions • Wastewater treat- ment sludges • Base metals |

| Chemical Conversion Coatings | • Dilute metals • Dilute acids | • Metal ion-bearing mists • Acid mists | • Metal salts • Acid • Base wastes | • Spent solutions • Wastewater treat- ment sludges • Base metals |

| Electroplating | • Acid/alkaline solutions • Heavy metal-bearing solutions • Cyanide-bearing solutions | • Metal ion-bearing mists • Acid mists | • Acid/alkaline • Cyanide • Metal wastes | • Metal • Reactive wastes |

| Plating | • Metals (e.g., salts) • Complexing agents • Alkalis | • Metal ion-bearing mists • Acid mists | • Cyanide • Metal wastes | • Cyanide • Metal wastes |

| Miscellaneous (e.g., polishing, hot dip coating and etching) | • Metal fumes • Acid fumes • Particulates | • Metal • Acid wastes | • Polishing sludges • Hot dip tank dross • Etching sludges • Scrubber residues |

| Document Title | URL |

| EPA RCRA Delisting Program Guidance Manual for the Petitioner, US EPA, March 23, 2000. | http://www.epa.gov/region6/6pd/rcra_c/pd-o/delist23.pdf |

| Delisting Risk Assessment Software | http://www.epa.gov/Region5/waste/hazardous/delisting/dras-software.html |

| Guidance for Quality Assurance Project Plans - EPA QA/G-5, EPA/240/R-02/009, December 2002 | http://www.epa.gov/quality/qs-docs/g5-final.pdf |

| RCRA Hazardous Waste Delisting: The First 20 Years, U.S. EPA, Office of Solid Waste, June, 2002 | http://www.epa.gov/osw/hazard/wastetypes/wasteid/delist/report.pdf |

| User’s Guide Delisting Risk Assessment Software (DRAS) Version 3.0, October 2008 | http://www.epa.gov/Region5/waste/hazardous/delisting/pdfs/dras-uguide-200810.pdf |

| Step Number | Description of Step | Approximate Time to Complete (months) |

| 1 | Identify constituents of concern and hazardous waste characteristics | 3-6 |

| 2 | Identify constituents of concern for special waste categories | 3-6 |

| 3 | Conduct an engineering analysis to complete your list of constituents of concern | 1-2 |

| 4 | Use generator knowledge to identify constituents of concern that ARE NOT in the waste | 1-2 |

| 5 | Identify Analytes | 1-2 |

| 6 | Select appropriate analytical methods | 1 |

| 7 | Identify appropriate QA/QC methods in a quality assurance project plan (QAPP) | 1-2 |

| 8 | Gather data following the approved sampling & analysis plan | 1-2 |

| 9 | Analyze data, run the DRAS risk assessment model, and begin preparing your delisting petition | 3-6 |

| 10 | Submit delisting petition to appropriate regulatory agency | 3-6 |

| 11 | Regulatory agency prepares proposed rule and publishes it in the Federal Register, for example | 3-6 |

| 12 | Regulatory agency prepares final rule and publishes it in the Federal Register, for example. At this point the waste is delisted and can be disposed as a non-hazardous waste. | 2-4 |

| TOTAL TIME | 23-45 |

| Section | Purpose |

| Executive Summary | Summarize the petition |

| Certification Statement | Certification Signature by Plant Manager per requirements at 40 CFR 260.22 |

| Administrative Information | Facility level information – e.g., location, contact information, waste identification, and requested action to delist a certain number of cubic yards of waste |

| Waste and Waste Management Historical Information | Basis for waste listing, historical waste handling procedures, and waste generation rates |

| Facility Operation | Overview of manufacturing operations, overview of pertinent systems, and overview of wastewater treatment plant systems |

| Chemical Review | Review of MSDSs |

| Waste Sampling Procedures | Procedures for sampling the waste and exceptions |

| Analytical Methods | Methods used to analyze waste samples |

| Summary and Discussion of Results | Statistical analysis of results and input of results into the DRAS model. Results are summarized and a PASS or FAIL decision is made. |

| Conclusions and Recommendations | Conclusions and Recommendations |

| Appendices | Include any significant correspondence, chemical reviews, data validation reports, and validated data results. |

REFERENCES iUnited States Code at 42 USC § 6903 (5). iiSee 40 CFR 261.3 iiiFor Appendix VIII see 40 CFR 261 and for Appendix IX see 40 CFR 264. ivTest Methods for Evaluating Solid Wastes – Physical/Chemical Methods vGuidance for Quality Assurance Project Plans EPA QA/G-5, EPA/240/R-02/009, December 2002 viUser’s Guide Delisting Risk Assessment Software (DRAS) Version 3.0 October 2008 U.S. viiEPA Region 5 Chicago, Illinois viiEPA. 1995b. Metal Plating Waste Minimization. Arlington, VA: Waste Management Office, Office of Solid Waste. BIO Bill Miller III, Ph.D., is a senior client program manager with Shaw Environmental and Infrastructure in Corolla, N.C. He has more than 35 years of environmental engineering experience, mostly dealing with delistings. You may reach him by phone at (252) 453-0445 or via e-mail: bill.miller@shawgrp.com.